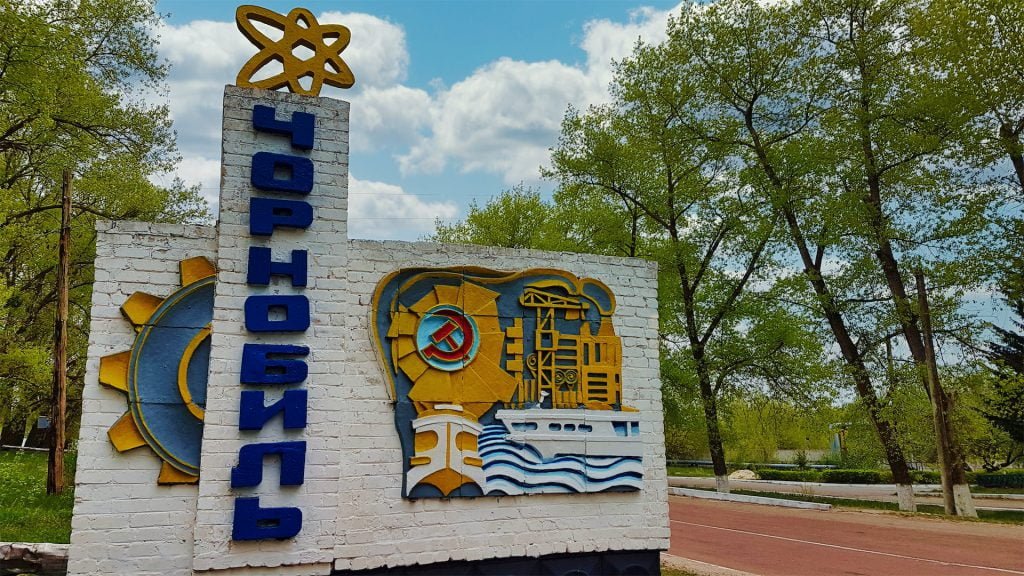

Chernobyl.

If you’re of a certain age just that one word brings to mind half-remembered TV news images and terrifying headlines. Nuclear meltdown. Radioactive fallout. Scary words.

As a child, Ukraine sounded like the other side of the world, and the Soviet union’s grip on information back then meant it may as well have been. When the disaster happened, information came out slowly. Eventually the world moved on, and now it’s a tourist attraction, a popular day-trip from Kiev, and it’s really not all that far away from home.

Standing in the abandoned town on a street being overtaken by nature, tarmac crumbling, apartment buildings looking beaten up and mostly missing windows, an unsettling silence all around, those TV news images keep popping into my head. Trevor Macdonald. Peter Sissons. Names and faces I haven’t thought of for years. I can even picture the old-fashioned TV news studio with one presenter sitting behind a grey desk like they used to do before they decided it would be more natural if it looked like they were in your living room with you and sat them all on sofas…

The town is actually called Pripyat. The town of Chernobyl itself is some distance away, but Pripyat was just a few km from the reactors of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and was once the prestigious new town where all the reactor’s staff and their families lived. Pripyat was a sought-after posting for the Ukrainian workers of the Soviet Union. It was a brand new model town and the young men and women who brought their families here were relatively well-paid and very proud of their ranking. For the citizens of Kiev lucky enough to have a relevant education, Pripyat was the prize they all wanted.

Pripyat was far more modern than the rest of Ukraine at the time, with ample schools, supermarkets, swimming pools, parks. It was the pride of the politcal elite. And it was suddenly abandoned over just a couple of days.

In the early morning of the 26th of April 1986, the reactor power systems were intentionally shut down as part of a test of the safety systems that went wrong. The core of reactor number 4 overheated and exploded, blasting away the roof and throwing plumes of radioactive material 2km into the air. The reactor core fire burned in open air for 9 days, releasing more radioactive material that spread all the way to western Europe and even Iceland. The amount of radioactive material released was 400 times more than at Hiroshima. Chernobyl and Fukushima are regarded as the worst nuclear disasters in history.

You may expect to find a dusty old town just missing its people, but the most striking thing now is how nature has taken over. It’s been 34 years and the trees are winning. It looks less like a hastily abandoned town and more like a military training zone or the setting of a zombie movie. If you play a certain computer game, you will recognise it instantly.

It occurs to me that if you could set up a paint-ball business here, you’d make a fortune. It turns out that the Ukrainian Army uses parts of Pripyat for military exercises. Bullet holes in walls and windows are becoming an increasingly common sight in visitor’s instagram stories.

The buildings are crumbling now. Windows all gone, floorboards collapsed. The football stadium field is now full of poplar trees. The roads have been lifted into bumps and ridges by the spreading tree roots, and puckered with holes simply from the actions of weather.

No cars pass this way anymore.

The forest is taking over. Once wide open streets with manicured public spaces are filling with trees. The wildlife is flourishing too. Wolves, moose, deer, bison, horses, even bears, all have reached numbers unheard of during the period of human occupation, now that they have a 30km / 18 mile exclusion zone all to themselves. No people. No industry. No Hunting. Radiation levels are now fairly low and although you wouldn’t want to drink the water, the animals are thriving. There are even giant catfish swimming in the old cooling rivers around the power plant.

A huge area of land is now one giant biology and ecology experiment.

Wild dogs and cats, too, in large numbers. All descendants of family pets left behind along with every personal possession when the town was suddenly evacuated.

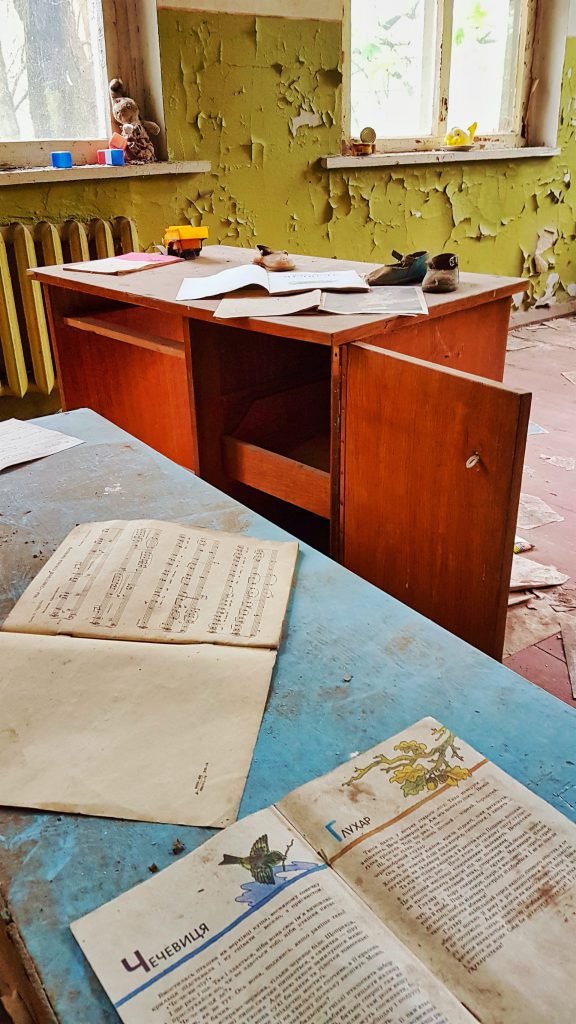

Cars, TVs, clothes, children’s toys, treasured photos. Everything was left. Everything.

Imagine it. Imagine a convoy of military vehicles in your street, instructions shouted over tannoys. You leave everything where it is, walk out of your house carrying nothing, and never return. Just like that. Imagine standing up, right now, walking out of your house, and never coming back.

Exact numbers are unknown due to propaganda and the fall of the Soviet Union, but around 100,000 people were evacuated. 2 staff were killed in the initial explosion and 28 of the 134 first responders died of acute radiation sickness in the months afterwards.

At least 600,000 liquidators were drafted in from across USSR to push radioactive material off the reactor roof with shovels for no more than 2 minutes because of the extreme radiation. Many later died or suffered cancers and other life-changing health problems. Estimates of deaths attributable to the disaster are still widely disputed due to the difficulties of documenting, verifying, and analysing the statistical data, but range from under 100 to as many as 16000 deaths.

The lack of life, the empty silence, the encroaching wilderness, makes you start picturing yourself a lone survivor in one of those post-apocalypse disaster novels. Silently, slowly, walking through the broken streets, alert to any sound in the trees. Vigilant for attacking wolves. Watchful for the moment when a deer may step into view, a target for your arrow.

It’s so easy to become engrossed in this fantasy because Pripyat doesn’t just look a bit like a scene from a post-apocalypse movie, it actually is a post-apocalypse environment. That’s exactly what the Chernobyl disaster was. An apocalypse. In these few dozen square miles, human existence was erased. Simply switched off. Emptied, lost, returned to the wolves.

Chernobyl and Pripyat is a photographer’s dream, but more importantly it is very poignant and thought provoking. You’ll get some great photos, but you will also have an experience so powerful you will never forget it.

Our tour guide calls us back together and leads us between the trees towards one of the decaying buildings.

“OK, this building was the school. We will go in here but please listen. It is against the rules to go inside the buildings. If we are caught, I will lose my permit and my job. We will go in here and up the stairs. Watch where you put your feet because there are holes in the floor. Do not go through any of the side doors because the floor may collapse. Follow me only. We will leave on the other side. Please stay together, and if there is any police coming we must leave immediately on the other side. OK? Let’s go”

I wonder if this is just a spiel for the tour group, to make it sound more adventurous, or is he really breaking the rules? It doesn’t actually matter, because it’s already exciting, and thrilling, and fascinating. You also quickly get the impression that following the guide’s instructions is a good idea.

You will see in places leftover items like children’s dolls or school books that someone has obviously moved into a position where it makes a dramatic looking photo. The place is already dramatic enough, but people will do anything for a photo, including touching things covered with radioactive dust. I’m sure plenty of people have also tried to shove something in their pocket and sneak it out as a souvenir. If you really were dumb enough to risk putting some plutonium next to your privates then you’d be in for a shock when you try to leave the exclusion zone.

Everyone has to pass through a radiation detector, to ensure that they don’t take out any contaminated items. Even the dust on your shoes can set off the detector.

The guide tells us the story of the girl who got tired on the tour and decided to sit down on the floor. She was stopped at the radiation detector, had to leave her trousers behind, and travel back to Kiev on the tour bus in her underwear.

These may all just be stories to help stop people trying to pinch the remaining relics that now serve to support a booming tourist industry, but do you want to take that chance? I’d prefer not to lean against the wall or sit on the old school desk, and keep my clothes for the journey back to town.

At some locations, our guide stops to show us period photographs of part of the town as it was before the disaster. The supermarket. The hotel. The main road in the very centre of town. It’s simply fascinating to see how far nature has taken over. With concrete and nuclear power, humankind can reshape the planet, but look what 30 years of nature can do.

Nearing the end of our walk around the town, our guide announces that the next stop is the fun fair. This is the bit lots of us have been waiting for because it is the iconic image of Kiev. The Ferris wheel and the bumper cars, gathering dust. You almost expect the lights to come back on and the wheel to start turning again, while the music slowly winds back up to speed. In reality, the wheel never turned. The funfair was due to be opened on the 1st of May 1986, so nobody ever rode the ferris wheel and no-one ever drove in the dodgem cars.

It’s been a few hours but it seems to have gone in minutes and the tour is over. The tour of the town, anyway. Still time for a photo call outside the sarcophagus now covering the remains of reactor number 4, a visit to a memorial showing the names of all the towns and villages that had to be evacuated after the meltdown, and a quick call at a fascinating graveyard of robots that were brought in from across the Soviet Union for use in the cleanup. One of the robots was being developed for a lunar mission, but instead was used to recover highly radioactive debris that had been blown out onto the roof of the reactor when the core exploded. We also get to see a former Soviet Union radar listening station. The Duga “Over The Horizon” radar station is relic of the cold war that bounced radio waves off the outer edges of the atmosphere to be able to “see” around the curvature of the earth and detect missiles being launched from England.

Some illegal explorers climb to the top of Duga at dawn to watch the sun rising over the exclusion zone wilderness. I doubt your guide will let you try.

You’ve probably seen it on TV. Maybe you’ve played that computer game. Perhaps you think it’s tacky, or perhaps you think it’s too hard to get too. You’re wrong. It’s captivating, it’s atmospheric, it’s thought-provoking, and it’s a surprisingly easy trip to make.

It’s so quiet, in what was once the pride of the USSR. You walk around entirely safe in a place where hundreds or maybe thousands of young soldiers, pilots, miners, fireman, nurses and others received radiation doses during the cleanup that meant they died before they were 40. Many brave people gave their lives in order to save others. There are no words to do that justice. Is it voyeurism? Some people may arrive with no thought other than to get some good shots for their insta, but they won’t leave thinking about that. They will leave thinking about the heroism and the sacrifice, the injustices and unfairness of the Soviet state, and a sense of how fortunate they themselves really are. That sort of insight is why we travel.

Even with your tour group it’s so quiet in the streets of Pripyat that you will have that spine-tingling feeling of unease, a vague disquiet that unsettles you without really knowing why. Ever watched a horror movie and even though your rational brain knows that there definitely is not an axe murderer creeping into your house, you still get that chill on the back of your neck and have to look behind you? Welcome to Pripyat!

Pripyat is just over 100km from Kiev, near Ukraine’s northern border with Belarus. It’s a 2 hour drive from the capital and there are several options for guided tours. It’s illegal to enter the exclusion zone without a guide.

I travelled with Solo East, booked through Viator.

Further reading